Featured image by Poswiecie: “Sigiriya, Sri Lanka.” September 24, 2014. https://pixabay.com/images/id-459197/.

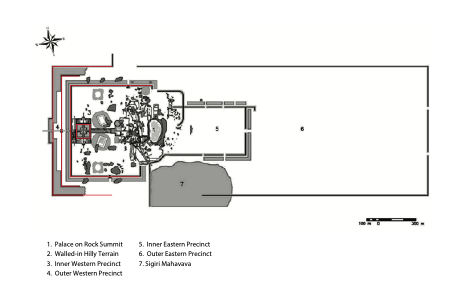

Deep in the northern dry zone of Sri Lanka, a large peneplain stretching from the southern mountains to the Bay of Bengal is home to the inselberg known as “the Lion Rock” (fig.1). Today, the granite monolith is home to the ruins of a Theravāda monastery and the city of Sigiriya, whose physical forms were directly influenced by seemingly paradoxical ideologies of religious and political power. Working primarily off the writing of Nilan Cooray, whose publication is found in the journal, Architecture of the Built Environment, I will highlight the history of the site as it was influenced by Buddhism and monarchy. Cooray’s publication is extensive and hints to the ideological frameworks utilized in the site but does not plainly discuss the relationships and connections between those ideologies. I posit that the forms found at Sigiriya are the direct result of the fusion between symbols of Buddhist cosmology and ideology with monarchical symbols of power and influence.

Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, came into his enlightenment between the 4th and 5th centuries BCE. While his teachings stray from the Vedas, their roots still lie within the hierarchical social structures of Hinduism. For instance, the Buddha claimed that enlightenment was attainable to all, without having to go through the rituals guarded and performed by the Brahman class. Despite this apparent call for collective liberation, Buddhist India kept the caste system “…with the king at the apex and Buddhist monks acting as the spiritual guardians of the nation…”, essentially replacing the Brahman class in the structures of power.[1]

One such Buddhist leader was Emperor Ashoka who converted to Buddhism in the 3rd century BCE, bringing the rest of the empire with him through the dispatch of monks as missionaries across eastern Asia. The two major schools of Buddhism, Therevāda and Mahayana branched during this migration, with Theravāda, the orthodox form, taking hold in Sri Lanka. During this new cultural paradigm, the role of the king shifted from being defined by dharma (cosmic order) to being devoted to the Buddha, justice, and public welfare. According to Cooray, “This favored immensely the creation of a landscape dominated by religious structure and public works.” And indeed, most of the architecture present in Sri Lanka to this day is from this period of building for the practice Theravāda.

Therevāda monasticism is characterized by highly ascetic practices including self-denial, fasting, elective poverty, removal from society, and a strict set of behavioral rules to follow. [2] Some of the first expressions of this monastic life took the form of forest sangha (Buddhist community) settlements in rock and cave dwellings, many of which are found at the western base of Sigiriya. Evidence of monastic life is found in drip ledge cuts above the mouths of caves as well as the inscription of donors’ names on the interior (fig. 4). This settlement was the first stage of intervention at Sigiriya and followed the dominant attitude that “…promoted the least human intervention in the natural landscape…” .[3]

Sigiriya as it is seen today was laid out by a King Kasyapa of the 5th century CE. Kasyapa’s claim to the throne was inherently challenged by the fact that he was the illegitimate son of the king and had taken the throne by force after a coup during which he sentenced his father to death. Following these dramatic events, he recentered his seat of power at Sigiriya, constructing a palace on top of the rock.

These call for citadels being placed in the center of “…several concentric precincts fortified by walls and entered through gateways facing cardinal directions…”, a form that is found in the Sigiriya plan. [4] The structures, however, are not excessively defensive. The entire city is surrounded by a wall behind which is a dug moat followed by another wall. This square within a square form (fig. 4) was a common organizational method, aligned with religious writings, and from the period when kings were supposedly devoted to public works. Therefore, far from being an isolated hiding place, Sigiriya was intended to be a city and religious monument.

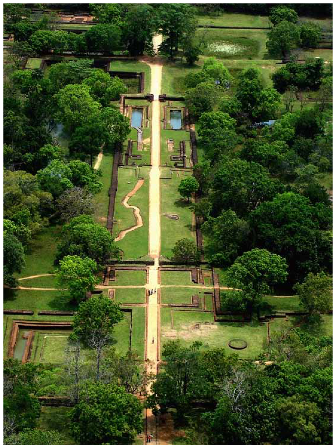

This is further enforced when considering the main cosmological world order of Buddhism, defined by the mythical Mount Meru, “…which lies at the center of the universe [and] is thought to be the axis mundi joining the earth with abodes of the Brahmas at the highest planes.” [5] The lion rock lies at the center of the site and is bisected by a strong east-west axis (fig. 5) that leads to the western precinct; the gardens. The eastern precinct is unexcavated but thought most likely to be residential. The alignment of the site to the cardinal directions, the centering of the lion rock, and the fact that the palace is raised up as if it were “[the] heavenly abode of god Sakra …on the summit of Mount Meru,” converge symbolically to align King Kasyapa with powerful forces, reinforcing his own power. [6]

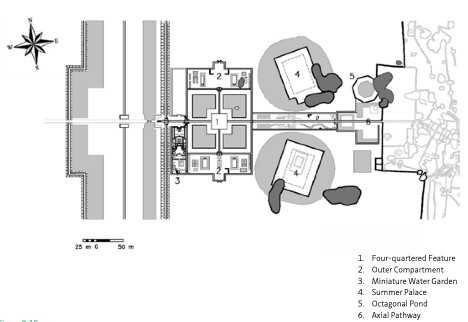

The gardens in the west consist of the boulder garden (former homes of the monks), a symmetrical and formal water garden, and a four-quartered garden that strongly resembles the char bagh, found in Persian paradise gardens, though it predates these (fig. 6). The north of Sri Lanka, which endures severe drought during the dry season (see fig. 2) had by the 5th century, well-established public irrigation systems and reservoirs. [7] One such reservoir is located in the southeastern corner of the lion rock and is the main supply of water that feeds the flowing, tiered fountain system in the water garden. While the form of the gardens is aligned with the puritan aesthetic ideals of the orthodox Theravāda and relies on simple, harmonious proportions rather than ornamentation, the water gardens also contain a number of facilities that connote the use of the space for pleasure.

Moated islands set on the north-south axis perpendicular to the main water garden have the foundations of summer palaces (fig. 7). The gardens contain hydraulic and gravity powered fountains as well as swimming pools and changing rooms. Kasyapa displayed a frivolous but ordered control over water, a precious and important resource, further symbolizing and communicating his power. I claim that Kasyapa was less concerned with a defensible place than with using the cosmology and symbology of Buddhism to persuade and convince the People of his claim to the throne.

Kasyapa’s rule was short lived, however, (just 18 years) and Sigiriya eventually returned to being a monastery. During this time, a few additions to the boulder garden were added, including an octagonal pool at the base of a boulder, as well as a bodhigara, the re-creation of the sacred tree under which Buddha attained enlightenment. These small but significant symbols reground Sigiriya as a primarily Buddhist monastic sacred space. Since its establishment by Siddartha Guatama, Buddhism has contained dualities created by the clash between its proposed ideology and the social forces with which it interacts. As with Jesus Christ, Siddartha was a reformer of a dominant religion, and while he drastically changed many aspects of societal structure, the force of the caste system and the players who upheld that system adapted and reworked the lessons in such a way as to allow for the continuation of the social hierarchy. This tension between power structures and spiritual ideology come to fruition in a place such as Sigiriya, collaboratively built and adapted over hundreds of years.

Notes

[1] Jude Nilan Cooray, “The Sigiriya Royal Gardens: Analysis of the Landscape Architectonic,” Architecture of the Build Environment No. 6 (2017): 43.

[2] Bhikkhu Ariyesako, “The Bhikkhus’ Rules: A Guide for Laypeople,” Access to Insight, The Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, 17 December 2013. Accessed 30 November 2020.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/ariyesako/layguide.html.

[3]Jude Nilan Cooray, “The Sigiriya Royal Gardens: Analysis of the Landscape Architectonic,” Architecture of the Build Environment No. 6 (2017): 44. Accessed Nov. 27, 2020.

[4] Ibid, 52.

[5] Ibid, 45.

[6] Ibid, 45.

[7] Patrick Bowe, “Making gardens and designed landscapes in the first millennium CE,” Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 40: 3-4 (2020): 312.